Thoughtful 8th Grader

My daughter, Tate, begins school next fall. What will her experience be as she navigates the dangers of growing up in an increasingly mean world?

I teach because I have to. In all the jobs I've had to pay my way through life, only teaching has (as of today) not left an empty feeling. This is my calling; and sometimes I feel that I chose to teach as much as teaching chose me. *Note: The thoughts expressed here are my own and not intended to represent the school or district I work for.

Last Sunday, the Hartford Courant ran a less than educational education article on Windham Public Schools titled "Windham Schools: Moving in the Wrong Directions." Clearly, the Courant felt it necessary to mislead its readers for the sake of selling papers or getting hits on the website. Though the article does express some of the realities of the school district, writer Grace Merritt chose to focus her readers on the visible effects of the many issues, but she failed to connect the dots between them. I've examined the article and found eight areas of foucs: Race, Poverty, Language, Parents, Teachers, Academics, Politics, and School Culture. Of the school culture, the Courant reports: "Teachers grumble that many students are disrespectful and roam the hallways during class... During a recent visit to both schools, some students were wandering in the hallways during class and had to be told by their principal to return to class. A couple of students yelled and cursed loudly as they passed in the hallway... During class, students often text or talk on their phones and sometimes swear at teachers." A school's culture will deteriorate when the norms of the school community are not shared by all. When student groups feel marginalized, or when students do not intereact outside of their group, a school's culture breaks down. Great schools recognize the basic need of human nature, which is to feel community. Windham's school climate issues are in line with many urban schools filled with students who have been marginalized for one reason or another. Certainly the effect, the "disrespectful" and "wandering" students, is visible and problematic. What is less visible, and less likely to get talked about are the causes. We cannot deny that the race, poverty, language, parents, teachers, and academic issues are not interrelated. To simply look at the effect and judge demonstrates a simple minded approach. But what can schools do to help alleviate the negative effects of these intermingling problems? In some ways, public schools should look to their competition for answeres; the charter school movement, and especially the successful ones, recognize that students must want to be at the school if they are to succeed at educating the student. Schools need to make a conscious effort to build their community by focusing on the norms and values they desire. Moreover, this conscious effort must be adopted by every school in the district. To expect a high school to recover the lost years in such a short amount of time demonstrates the type of simple mindedness that leads to state takeovers of schools. Here I offer three simple ways a school or district can begin changing the culture. There are many additional methods (like the Broken Window theory), but I write a blog, not a book.

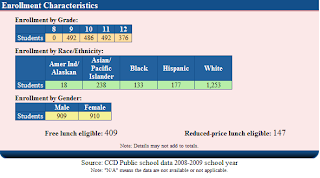

Fixing a failing school district requires thoughtfulness and understanding much more than empty rhetoric and theorizing. So, I wonder what brings a journalist to only explore the world of education on a surface level. According to the Hartford Courant, Windham Public Schools are headed in the wrong direction. At first glance, there may be some truth:

One of my long ago friends' father is the world's nicest man. He uses phrases like "oh my gunnysacks" and others I never fully understood. What I recall most fondly about him was his honest appreciation for his wife. On more than one occassion, I had the opportunity to dine with his family, and without fail, my friend's father, after finishing the meal, would declare "Cathy, this was the best...you've ever made." No matter what the meal. Grilled cheese--the greatest. Peanut butter and jelly--the greatest.

During our CAPT days, I've been working my way through John Merrow's The Influence of Teachers: Reflections on Teaching and Leadership. Although the regular monitoring of students has slowed down my read, one chapter, "Serious Fun?" forced me to evaluate the methods of the two schools I've taught at.

There, a true partnership between students and faculty existed. Merrow discusses Ted Sizer's belief "that schools...should be democratically run, and that high school kids should be part of the leadership."

Once, after I had moved, I had the opportunity to visit that school during what turned out to be a spirit day. The majority of the student body were participating by wearing school colors or class colors. When I taught there, I recall the nearly monthly assemblies or pep rallies, all of which were led by student leaders. They planned and oversaw each activity. That campus had a palpable heartbeat shared by so many of the faculty and students.

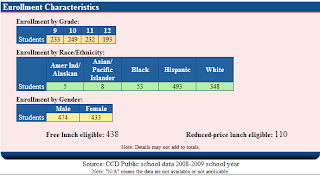

My current school looks as follows:

Here, students are not given the opportunity to come together or to lead each other. We have had one all-school pep assembly, which happened during our homecoming week. My sophomore class officers and cabinet helped me put together a pre-CAPT pep assembly that went as well as it could considering we were celebrating a test! We received great feedback from students and teachers.

If my current school stepped out and took the risk of truly engaging students in leadership roles, could we turn around the ever-growing negativity which permeates our hallways? And ultimately, what is getting in our way?

Do we fear that "these" students will not know how to behave? Do we fear giving up control to teenagers? Do we think the current building atmosphere is positive and empowering?

Students will act how we expect them to act. If we took the time to collectively teach, monitor, and enforce our expectations, our students will generally conform. Yes, some students will still make poor choices. That's when strong leadership deals with the student accordingly. We like control. I know I do. This is a constant struggle for me. But when I empower my student leaders, they find success. And no, I can't imagine we believe the current climate is anything but demoralizing.

My sophomores took the Response to Literature test today, and too many didn't finish writing the fourth essay in the 70 minute time frame. But, they told me how they answered the first three, rife with quotations and explanation to fill up each page provided. They felt great about what they had written, but depressed that they hadn't finished in the time frame.

I gave in yesterday. The day before the state exam, and after two weeks of heavy test preparation, I allowed my students to relax. I gave them a few final reminders and then allowed them to have "free" time.

"Gentleman, start your engines," or in our case, "Students, start your brains." This week Connecticut's version of high-stakes testing begins its annual takeover of public education. Testing is important, don't get me wrong; I'm just not sure what we learn from them that we don't already know.